1912 Packard Model 30

April 24, 2020

By Derek Hill

In 2013 I had an inquiry from Chasing Classic Cars TV host Wayne Carini, wanting to visit my late father’s garage in Santa Monica to profile some of the family cars we had held onto. I enthusiastically said “yes” and, in no time, a film crew showed up. The timing was good, as I had just been told the family’s 1912 Packard Model 30 was accepted to the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, which was coming up in a few months.

If any of you tuned into that episode of Wayne’s show you will have seen me in the garage trying time and again to start the cars. Anyone in the classic car world knows that cars don’t get better by sitting idle, and it had been perhaps longer than I had thought since I had taken any of them for a drive. I think the mind plays tricks on you: you remember that the last time you drove a car everything ran just fine right up until you parked it back in its spot and shut it off. So why won’t it just start right up again? Anyhow, Wayne’s crew captured some fairly comical footage of me draining batteries while trying to start up the 1931 Pierce-Arrow and the 1912 Packard — with very little success. We did finally manage to get the Pierce-Arrow running and had a nice drive around the neighborhood filming and talking about the car. However, when the crew left, I wasn’t happy about the state of the cars nor how this episode of CCC was shaping up — especially when I realized how much work needed to be done to get the 1912 Packard ready for the Concours!

Luckily, this was only the beginning of the story and I had time to get things right; the Concours was still a few months away and Wayne and his crew would be there to follow up on the episode. My frustration that day in the garage was channeled into extreme motivation to make things work as they should.

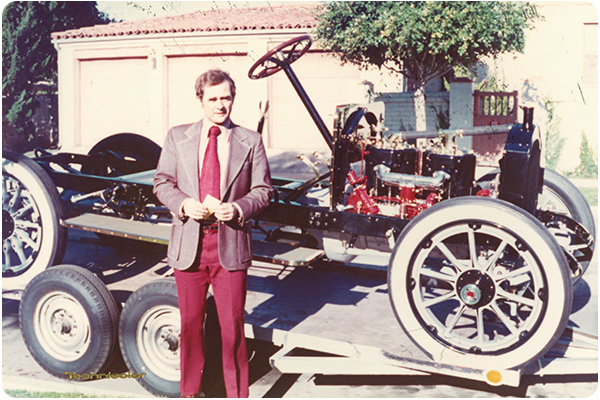

The 1912 Packard is a truly beautiful show-quality specimen, a car my father had restored to perfection some 44 years earlier. He had bought the Model 30 as a project car out of the Rod Blood Collection, which was all sold at auction in the late 1960s. At that point in my father’s life, he had just retired from a stellar career as a racing driver and was starting on his next chapter as a car restorer and soon-to-be family man. In my own memories of the 1912 Packard, formed years later, it was always sitting in the garage but never driven. When I would ask my father why we never took that car out, his answer was always that it was simply in too good a condition. He would show me the details of the car and have me crawl underneath and look at the pinstriping on the back axle’s differential housing. Yep, he was right; that car was immaculate. Not even the wicks were burnt in the kerosene side-lamps. It was a symbol of my father’s perfectionism — which, as I came to learn, was both a help and a hindrance. Shiny immaculate show cars of that era didn’t need a reputation as “cars you happily put miles on”; it was perfectly okay to roll an example like this off a trailer right onto a show field.

I was facing a different set of circumstances now: it was my turn to bring this car to Pebble, where it had appeared twice before in 1973 and 1999, but expectations had changed and now it would have to be in good driving condition. The car had been sitting idle for some 15 years in the coastal climate of Santa Monica, and when I rolled it out into the sunshine I realized just how much TLC it needed.

The sheer visceral experience of driving a car like this awakens the beauty and depth of craftsmanship from this era — especially in marques like Packard. Everything about the car at speed was solid, vibrant and — if cars could feel… happy.

DEREK HILL

The cork running boards were darkened, the brass was thoroughly oxidized, and the leather straps that secured the top were cracked and broken. The rear “Isinglass” celluloid windows in the leather top had faded to yellow and one was cracked. My own perfectionist mentality kicked into gear and I knew I had a lot of work to do. Not only did I want the car to look amazing, but I also wanted it to show that it enjoyed life on the road and ran well too.

One of the first things I did to break the mold of the past was to fill the gas lamps with kerosene and take a match to them to see flickers of light. That moment, as small as it may seem, was a big step forward for me. It defied everything my father had programmed into me mentally about his pride in that car and what it stood for. Even though my father was no longer around, I felt I was up to something mischievous. As those side lamps burned, a whole new beauty exuded from the car for me, and I was ready to get my hands dirty.

I employed a friend who had some spare time to help me out, and we started dismantling things like the throttle linkage in order to get the carburetor off and the valve on the fuel tank to switch over to the reserve. These things were thoroughly seized and in need of attention.

I had never been a car restorer myself, but the hours spent working alongside my father in the garage made me realize how much I actually had learned. I found it very enjoyable going from one thing to the next. And just as my father was still living his bachelor life when he restored this car in the late sixties with the little constraint to his leisure time, so was I. My evenings went late, stripping this car of anything that needed attention. I took the leather straps to a saddlery shop in East LA and in no time they were redone beautifully. An upholsterer put new windows in the back, and I tackled the running boards with some scouring pads and detergent. The evenings turned into weeks, with some Saturdays and Sundays thrown in. I understood for the first time the joy of restoring something to a renewed condition. I also realized how much one’s appreciation for a car can grow when you get so deeply involved with every aspect of it.

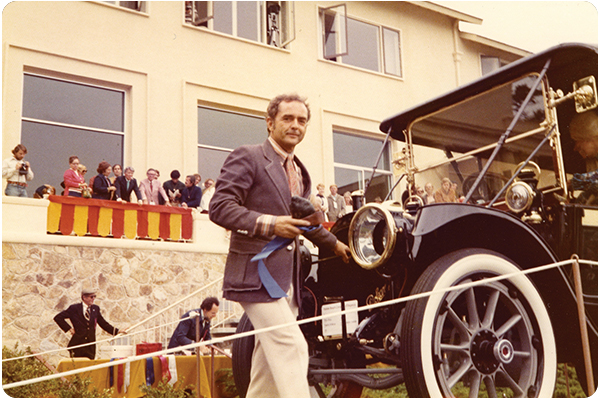

The moment when the car was named First in Class felt extraordinarily special; it was a moment of truly remembering and honoring my father.

DEREK HILL

Then it was finally time to get the car ready for driving. These 1912s were pre-electric starters, and for the inexperienced, hand cranking an engine to life can be slightly daunting. After running down the checklist — fuel on, car in neutral, prime the carburetor, retard the spark, set the throttle on the steering wheel, electrics off, crank over a few times with compression release pulled out, turn electrics to battery, and . . . crank! As soon as it fires up, run back to the steering wheel to close the throttle, switch over from battery to magneto, set the timing in the middle, and finally make sure oil is dripping down through the indicators. It is such a pleasure to hear an engine fire up under these circumstances and then to get behind the wheel!

I started taking the car out on longer and longer drives to see what might go wrong. After a few more adjustments to the carburetor and several journeys later, I was blown away by what a great driving car this was. Before long there wasn’t a hill it couldn’t conquer. The sheer visceral experience of driving a car like this awakens the beauty and depth of craftsmanship from this era — especially in marques like Packard. Everything about the car at speed was solid, vibrant, and — if cars could feel… happy.

In no time we were lined up with the other cars getting ready for the Tour d’Elegance. Wayne Carini was my passenger upfront and my mother, sister, brother-in-law, niece, and nephew were in the back. And the car ran flawlessly, as I knew it would. We even took it around Laguna Seca and down the corkscrew — what a thrill that was!

Come Sunday morning it was time for judging and, amazingly, all the hard work and practice paid off. I was able to delight the judges with a car that started right up. I even displayed the operating acetylene headlamps, complete with the ignitor accessory giving spark with the push of a button on the dashboard.

The level of attention a car like this needs in order to be ready for showtime might seem somewhat absurd but it was completely worth the effort. The moment when the car was named First in Class felt extraordinarily special; it was a moment of truly remembering and honoring my father.

After one last tweak to the acetylene gas headlights and a nighttime drive around the neighborhood with the flickering glow illuminating my way, I was confident that I was ready for Pebble Beach.

An Unmatched Tradition of Automotive Excellence since 1950

August 16, 2026 — Just 231 Days left!