Early Lincoln & the World of Art

June 15, 2022

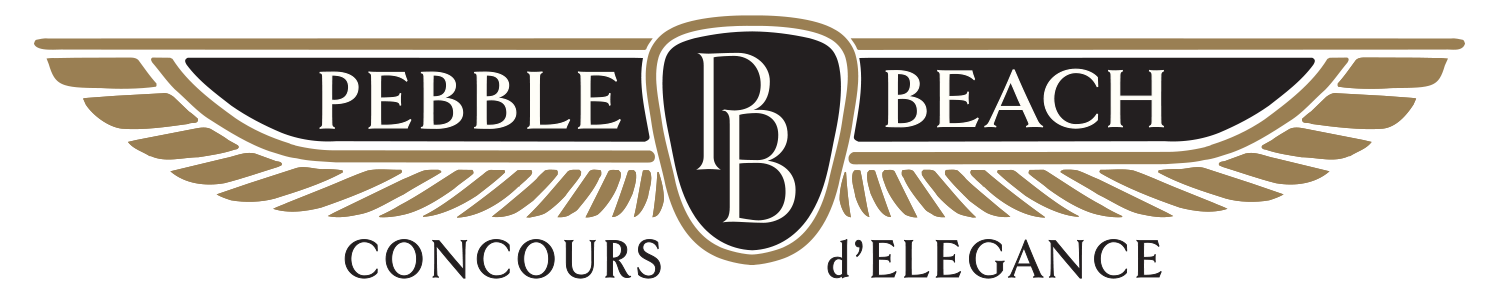

The Advertisements that Elevated Lincoln to a Luxury Marque

By Leslie Armbruster

From the moment that Lincoln was purchased by Ford Motor Company, the marque was destined to embody luxury. Lincolns were to be more than transportation; they were to be subjects and objects of art.

Edsel Ford, the only son of Henry, had argued for Ford’s purchase of Lincoln on February 4, 1922, and he was soon appointed to serve as its president, overseeing every aspect of production and perception. Edsel had an impeccable sense of style and design, and this was evident in everything he did, particularly in overseeing the development of Lincoln and crafting its public image.

The market was primed for a luxury car.

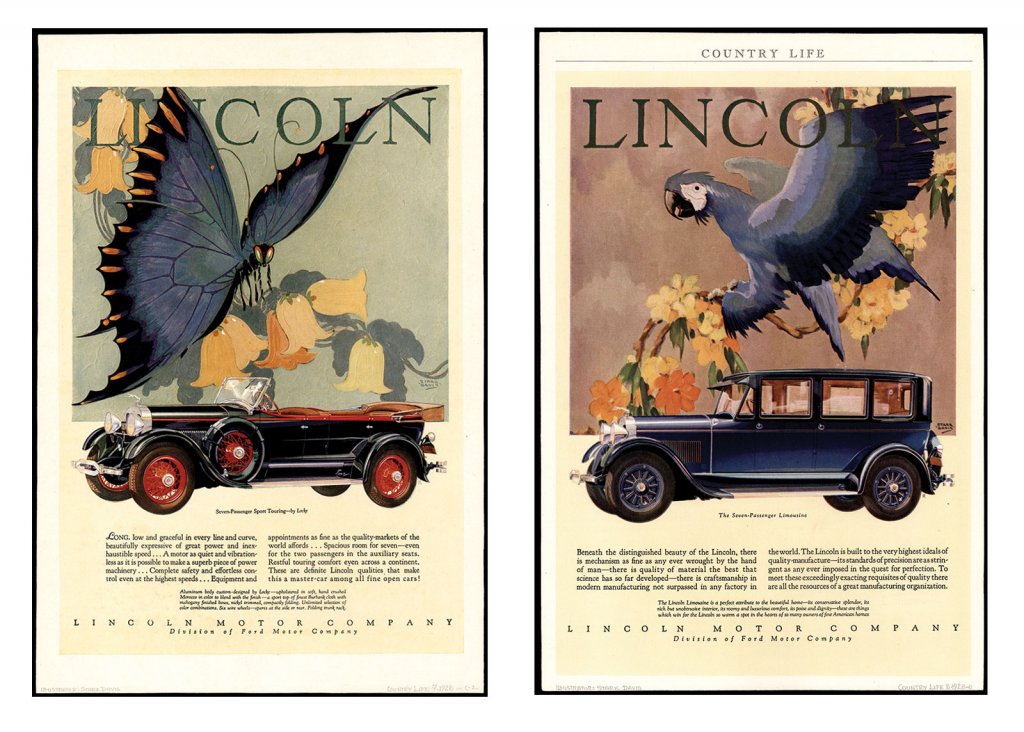

After World War I, Americans were ready to leave the trials and tribulations of wartime behind and embrace the opulence of the roaring ’20s. That trend was evident as magazines began to focus on wider circulations in the new culture of consumerism. Print advertisements became more prominent within the magazines and more artistic, often featuring beautiful images of high society, a peaceful home life, and bucolic outdoor settings. The intent was to illustrate all that society had missed during the war.

Popular artists like Norman Rockwell and Maxfield Parrish became household names when publications featured their art on covers and companies commissioned them to create original illustrations for advertising. At a time when illustration was not considered fine art in America, many artists turned to advertising contracts as a way to both make a living and gain an audience for their beautiful works.

Though color photography would not become mainstream in magazines until the mid-1930s, color printing was increasingly affordable for publishers in the early 1920s. Illustrators had the ability to be colorful and bright, while still being as factual as possible with their artful depictions of everything from food to automobiles.

The 1920s and 1930s were arguably the greatest years for creating works of advertising art. It was a time when the convergence of big advertising budgets, pools of great artistic talent, and hungry consumers created the perfect recipe for these wonderful works of art. Along with other companies of the time, Ford Motor Company and its Lincoln Division benefited from this wealth of talent by creating advertising that still speaks to consumers today, 100 years later.

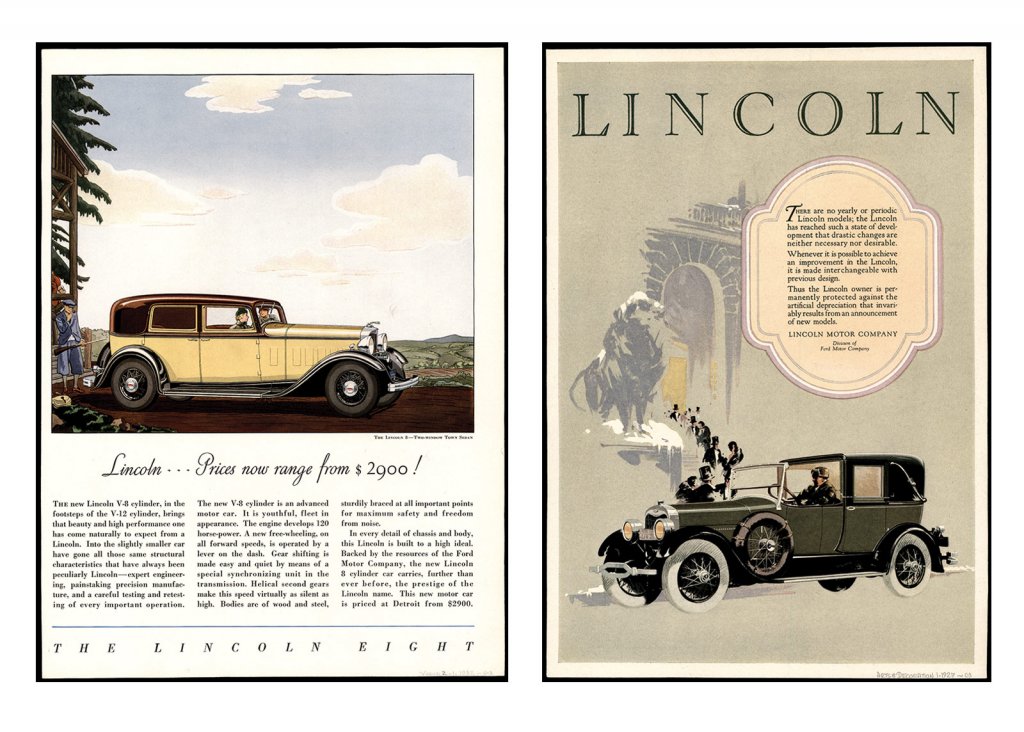

The birds and butterflies that William Stark Davis painted for Lincoln advertisements in the late 1920s represented optional color variations for a car, both inside and out. Davis went on to work for Walt Disney Animation Studios.

Edsel and his wife, Eleanor, were lifelong supporters of the arts, amassing an impressive personal collection of fine art, many pieces of which would be donated to the Detroit Institute of Arts after their deaths. During their lifetimes, they supported that and other artistic organizations, such as the Detroit Artists Market and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra.

The most prominent of Edsel Ford’s collaborations with the Detroit Institute of Arts was his patronage of Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals, a series of twenty-seven original frescos adorning the walls of an interior court of the museum.

Created in 1932 and 1933, the murals depicted the people and machines that had worked to create the automotive and pharmaceutical industries, and subsequent prosperity, in the Detroit area. A sea of machines, industries, and workers of all shapes, colors and sizes, the murals represent the heart and soul of the community. Rivera took a break from creating the murals to paint a separate portrait of Edsel Ford, choosing to honor his artistic spirit by depicting him in an automotive design studio, rather than a factory.

Edsel would eventually play a role in designing some of Lincoln’s finest offerings, including the Lincoln Continental and the Lincoln Zephyr. But from the very start, he focused on Lincolns as custom creations. And no doubt he had a say in choosing which artists would be selected to create beautiful advertising for the brand.

Many of the largest advertising agencies were based in Chicago during the 1920s, so Detroit’s automobile manufacturers had easy access to a large pool of both experienced and up-and-coming illustrators from which to choose. Ford Motor Company and its Lincoln Division engaged many different artists and illustrators to create imagery for their product advertisements during this era.

Oftentimes, one illustrator would create an elaborate background scene, while another drew the actual vehicle being advertised, highlighting optional equipment like wood trim, wire wheels, side-mount mirrors, and in the 1930s, radios, leather upholstery and custom luggage.

Artists frequently highlighted optional elements of the actual vehicles in a subtle way within their pieces. Take, for example, the work of Winthrop Stark Davis, better known as Stark Davis, who created some of the art for ads for Lincoln in the late 1920s. Born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1985, Davis based his career out of Chicago, where during the 1920s and 1930s, he created art for the Ladies’ Home Journal, as well as a wide variety of businesses, including the Ethyl Corporation. He would go on to work for Walt Disney Animation Studios in California, where he lived until his death in 1950. Perhaps his most famous pieces of advertising art are the various

imaginary birds—and one butterfly—that he painted for Lincoln. Each of his birds or butterfly represented optional colors for exteriors and interiors of Lincoln motor cars. Separate artists then drew the vehicles to appear with each bird in coordinating optional color schemes. The overall effect of this campaign was dramatic and elegant, which speaks to its enduring popularity.

Other artists utilized negative space to create a sophisticated feel in their advertising art. Campaigns by Haddon Hubbardm Sundblom, Frederick Smith Cole, and Floyd Curtis Brink

often demonstrated this technique. Their understated outdoor scenes were partnered with expansive backgrounds in soft, muted colors, which gave consumers time and space to reflect on the vehicles shown. This allowed them to imagine how these beautiful cars might enhance their lifestyles. The simplicity and stylishness of these advertisements can still be felt today.

Born in 1889, in Muskegon, Michigan, Haddon Hubbard “Sunny” Sundblom studied at both the Art Institute and the nearby American Academy of Art in Chicago, where he based his career. He is most known for the advertising art he created for Coca-Cola, helping to invent their version of Santa Claus, but he also worked for the United States Marine Corps, Proctor & Gamble, and Quaker Oats, among other companies—and he created many works of art for Lincoln advertising, often placing the cars in settings that offered hints of palatial dwellings, peaceful settings or favorite pastimes, including golf. Sundblom died in 1976, leaving behind a lasting legacy of beautiful work.

at the heart of Lincoln motor cars.

The art of Floyd Curtis Brink continued many of the same themes as Sundblom, and Brink’s creations might be mistaken for those of Sundblom although they often include somewhat more bold strokes and fewer details. Brink was born in Illinois in 1892, he studied at the St. Paul Institute of Art, and his art appeared in publications like Good Housekeeping and Ladies’ Home Journal. He created advertising art for several automobile manufacturers, including both Ford and Lincoln. He died tragically in 1935 when a plane flown by fellow commercial artist Albert Whitney lost one of its wings and crashed.

Born in 1893, Frederick Smith Cole attended the Art Institute of Chicago, and after fighting in World War I, he returned to Chicago to work as an illustrator. He would later move to Detroit and open The Art Studio with his business partner to be closer to automotive manufacturers. During his career, he created advertising illustrations for both General Motors and Ford, including the Lincoln Division. His work for Lincoln expanded on the themes initiated by Sundblom and Brink, showcasing the excitement and adventures of world travel,even pairing Lincoln motor cars with new airplanes. He lived in the Detroit area until his death in 1967.

Although Lincoln continued to create beautiful advertising for its products, like the Model K, Model KA, and Model KB, the use of signed artwork in its advertisements soon ended. The clean lines and geometric figures of Art Deco style, which were clearly apparent in some of the later Lincoln materials, were also used to advertise Lincoln’s all-new Zephyr in the late-1930s. The streamlined design and alligator-type hood of the Zephyr lent themselves beautifully to the Art Deco style. Economic challenges and technological advances of the day would bring this era of advertising art to a close by the end of that decade.

An Unmatched Tradition of Automotive Excellence since 1950

August 17, 2025 — Just 118 Days left!